The first symptom that sent Deleene Clarke to the doctor was a high heart rate.

In the fall of 2023, the 43-year-old started to feel unwell. She was having cold sweats and often felt like she might pass out.

And during these episodes, her heart would race. Sometimes it felt as though it might burst through her chest.

“You know those conga drums? It feels like somebody’s doing that to your heart,” Clarke says. “And then it makes you feel like you ran a marathon after it stops.”

Silenced symptoms

Downplayed. Dismissed. Devalued.

In this monthly Free Press series, we’ll explore underdiagnosed, underrecognized and undertreated health issues affecting the lives of women, nonbinary and trans people.

We will share stories and lived experiences, while also raising awareness.

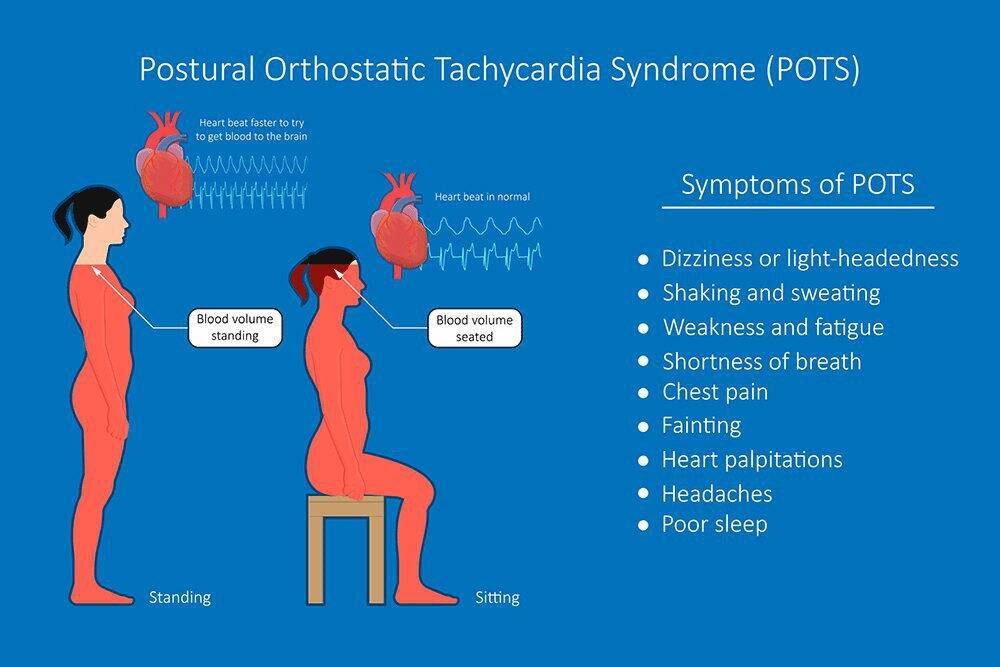

As she would find out many months, tests and specialists later, Clarke suffers from a disorder called POTS, or postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome, a condition that causes a person’s heart to beat abnormally fast when they stand up.

POTS is typically sudden-onset and persistent, and affects otherwise healthy young people — and, in particular, healthy young women.

“About 85 per cent of POTS diagnoses are made in women,” says Dr. Colette Seifer, a cardiologist at St. Boniface Hospital and a professor in the department of internal medicine at the University of Manitoba.

Seifer says POTS fits under an umbrella of disorders called dysautonomia, which means it’s an abnormality of the autonomic nervous system.

“The autonomic nervous system is responsible for lots of the body system processes that you don’t really think about, things like control of blood pressure, heart rate, sweating, digestion,” she explains.

When you stand up, blood is pulled down into your lower body by gravity. Your autonomic nervous system responds to this imbalance quickly via a series of processes to return blood back to your heart and brain — including the release of hormones that constrict blood vessels and slightly increase heart rate.

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press

It took Deleene Clarke many months of having tests and seeing specialists before she was diagnosed with POTS.

In people with POTS, however, those processes are disrupted. The blood vessels don’t respond normally to the hormones, which means blood has more time to pool in the lower extremities. The heart, still reacting to the hormones, will beat faster.

To make a POTS diagnosis, health-care providers will typically have patients undergo what’s called an active stand test. Patients have their resting blood pressure and heart rate measured, and then they are asked to stand for 10 minutes.

“We look for a sustained or continued increase in heart rate, in adults above the age of 19, of greater than 30 beats a minute from baseline, and have it sustained for that 10 minutes,” Seifer says.

For teenagers, it’s 40 beats a minute from baseline.

“Patients with POTS not uncommonly will have heart rates when they stand up somewhere between 130 and 160 beats per minute,” Seifer says.

To put those numbers into context, those are heart rates more commonly associated with aerobic or vigorous exercise.

But while the commonly used diagnostic test for POTS is simple, the condition can be difficult and time-consuming to diagnose, owing to a frustrating constellation of symptoms.

That racing-heart sensation, particularly on standing or doing any minimal activity, is the chief symptom of POTS, but lightheadedness, tremors, sleep disturbances, headaches, fatigue, exercise intolerance and brain fog are all typical of the condition, Seifer says.

The trouble is, those symptoms are also typical of a host of other conditions, so doctors often have to consider and rule out other things.

“Some of the symptoms are transient and resolve completely and are not POTS, so sometimes it can take some time,” Seifer says. “I do encourage health-care providers to do this simple 10-minute stand test to consider POTS as a diagnosis, because it can be done in the office very easily and can help assess it.”

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press

The first symptom that sent Deleene Clarke to the doctor was a high heart rate.

POTS, on its own, is not a life-threatening condition. But it is life altering.

“Many patients have very poor quality of life,” Seifer says. “There’s some difficulty frequently getting diagnosed, which can lead to patients feeling like they’re not getting care.

“In terms of risks of the condition itself, it doesn’t particularly damage the heart or the nervous system in any way, but it leads to chronic disease, essentially, and all the occurrences with chronic disease.”

Clarke was stepping out of the shower when her heart began to race again.

“I rushed to the hospital, but by then it had stopped, so when they did the EKG, everything came back normal,” she says.

Then Clarke started getting what she describes as weak spells.

“I started to bug my doctor now, so I kept going there, because I’m like, ‘Something is wrong, what’s going on?’”

Her doctor put her on bisoprolol, which is used to treat a variety of cardiovascular diseases, but she still wasn’t feeling better. In fact, sometimes she felt worse.

In December, Clarke was supposed to go on a cruise. Two days before her vacation, she went to urgent care to see if she would be OK to travel. The doctor who saw her there told her she might have a virus, or perhaps she was experiencing side effects such as fatigue from the medication.

“They ran all sorts of tests. They did every blood test possible, I think. My doctor had also sent me to do a bunch of tests.”

She was cleared to go, but the cruise was a disaster. Clarke got horribly sick — especially when she was on water. Her heart rate was starting to mess with her sleep, and she kept waking up with what felt like panic attacks.

Upon her return, Clarke saw a different doctor at her usual clinic who suggested she had depression and anxiety. Clarke pushed back and told him to do more tests.

Finally, she was referred to a cardiologist and received another EKG and ultrasound.

“And he was like, ‘Your heart’s perfect. I can’t see what’s happening.’”

But Clarke was struggling to get out of bed in the mornings. “I’d wake up and feel fine, but then I’d go downstairs to make the kids’ lunch, and I hardly can make it back upstairs.”

One morning, Clarke was, once again, in the shower when her heart began racing. This time, she had the presence of mind to grab her Apple watch. Her heart rate was at a staggering 225.

“And this was just me taking a shower,” she says.

In January, Clarke was diagnosed with SVT, or supraventricular tachycardia, and was referred for surgery — which, by some small miracle, she was able to get in for the following month.

But something still didn’t seem right.

“Of course, I’m on the internet, you know, trying to figure it out,” Clarke says. “I’m putting in all of my 100 symptoms, and every time I research SVT, there were some of the symptoms that were happening, but just a tiny few. It was like, ‘This is not it.’”

Still, Clarke went ahead with the surgery (which later revealed she also has a condition called atrial tachycardia). When the doctor came in to talk to her pre-op, she recalls, “I said to him, ‘I need to ask you something, though, before, because I’ve been having these symptoms, like when I get up in the morning, as soon as my feet hit the ground, I am just not OK.’

“And he was like, ‘OK, you have POTS.’”

Clarke was stunned. She had never heard of POTS. “Apart from ‘pots and pans,’ no,” she says.

“There I was, getting ready for surgery, Googling what POTS is. And everything became so clear.”

As for why POTS is more common in women, “the short answer is, we just don’t know,” Dr. Seifer, the cardiologist, says.

“There’s one theory that it may be an autoimmune condition, and autoimmune conditions are generally more common in women, and those are the conditions where you develop antibodies to normal body cells, and you can get a variety of symptoms and illnesses.

“So that’s one theory, but we don’t know,” she says. “But certainly all research evidence we do know is that it is more prevalent in women.”

POTS sometimes occurs after major surgery or after pregnancy, and often there’s a viral illness that precedes it, Seifer says.

To that end, there’s also growing evidence of a rise in POTS cases owing to COVID-19. About 15 to 20 per cent of patients who develop Long COVID will develop POTS, Seifer says.

“So it is common,” she says. “Some of the challenge, too, is that POTS can present similarly to other conditions like deconditioning you can get post-illness, some of the chronic fatigue disorders, some autoimmune disorders, so it can mimic some of those other conditions, also making the diagnosis a bit challenging, particularly in the post-COVID era.”

Erika Berthelot, 33, developed POTS symptoms after having COVID in March 2023, particularly a dizziness she couldn’t seem to shake.

“I couldn’t get out of bed without hanging onto walls,” she says. “As soon as I would get out of bed, I was dizzy and nauseous and lightheaded.”

It started to affect her ability to work. Berthelot is a nail tech, so if she doesn’t work, she doesn’t get paid. “I had to drop my clients down from at least six clients a day to three, and I was bailing on clients in the middle of their services,” she says.

Berthelot does not have a family doctor, so she’s had to rely on a patchwork of care. She saw one doctor who ordered blood work, but all her labs came back normal. She saw a vestibular physiotherapist, who ruled out persistent postural perceptual dizziness (PPPD) and suggested it could be vestibular migraine.

But like Clarke’s SVT diagnosis, vestibular migraine didn’t seem like an exact fit.

Berthelot knew her symptoms started after her COVID infection, so she posted about them in a long COVID group on Facebook.

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press

Erika Berthelot got an inkling of what might be causing her illness after writing about her symptoms on a long COVID group on Facebook.

“And these people started commenting, you have POTS, you have POTS, you have POTS,” she says. “And it was clear as day to everybody else, except for me. I’d never heard of this condition before.”

But the more she read up on it, the more POTS lined up with what she was experiencing.

“I would be lying in bed, and I’d be like, ‘OK, today is a new day. I feel good. I’ll be OK. I’m going to be able to function,’” she says. “And as soon as I would stand up to get out of bed, my heart rate would hit like 150 or 160, and I would feel absolutely crappy, and I could barely brush my teeth before I had to go lie down again.”

Obtaining a diagnosis has proven difficult, however. Berthelot says she was dismissed by a doctor for mentioning that her symptoms might be related to COVID.

“I went in and I just said, you know, my heart, I’m having dizziness, nausea, with a lightheaded sensation all the time, particularly when I stand up. This is my heart rate when I stand up. And here’s a history of that from my Apple watch. And this all started from COVID,” Berthelot recalls. “And she was like, ‘Well, that has nothing to do with COVID.’”

She then consulted a doctor on QDoc, a virtual health-care service. This time, she actually felt heard.

“This doctor was like, yes, I would agree you have POTS, which is great. I was given the half-ass diagnosis,” Berthelot says.

“But there’s no, ‘This is the plan, you will feel better. It’ll take X amount of time, you just need to do these steps.’”

There is no cure for POTS, but the condition can be managed.

Dr. Seifer, the cardiologist, says that the first step in treatment often involves assessing the patient for other conditions that might make POTS symptoms worse.

“So, we assess for anemia, we assess for diabetes, we assess for thyroid function. We assess for low vitamin B12 levels, for cortisol, the body’s naturally occurring steroid. We rule out any separate autoimmune disorder.”

From there, patients are encouraged to up both their salt and water intake. Salt plays a unique role in the management of POTS.

“There are many medical conditions where we do want to limit salt, but POTS is one where we do want to add salt to the diet — up to 10 grams, which is a teaspoon and a half,” Seifer says. “It really helps to preserve blood volume, because we think blood volume has a big role to play in this condition. Salt helps keep fluid inside the blood system.”

It’s recommended that POTS patients add salt to nutritious food as opposed to relying on processed food for this purpose.

Exercise is also an important part of POTS management, although Seifer acknowledges this is challenging.

“Patients already feel fatigued and have difficulty exercising, so we generally refer them to cardiac rehab, and they start on a program that involves exercise where you don’t have to stand — so things like a recumbent exercise bicycle, or a rowing machine, or swimming.”

There are also medications patients can take that are used to support heart rate and blood volume. Compression socks can also help.

Wearable fitness trackers that monitor heart rate — such as the Apple watches mentioned by both women in this piece — have made people more aware of their heart rates in general, Seifer says. They are a useful tool, but they should be used as part of a toolkit.

“They really do have their place,” she says. “They often help us manage heart rhythms in the longer term. But in terms of assisting with diagnosis in the POTS realm, you really do need to be seen and have the active stand done.”

Ruth Bonneville / Free Press

Erika Berthelot developed postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which causes your heart rate to accelerate, after having COVID-19 in March 2023.

About 50 per cent of people with POTS will recover, Seifer says.

“It can take a long time, though, and the improvement can be slow,” she says. “Some research suggests it can take up to five years to see full improvement in symptoms. The younger the onset of symptoms, the more likely that there will be a recovery as well.”

Living with POTS isn’t easy. Clarke has been increasing her intake of salt and water, lugging around an enormous water bottle. She’s taking medication, and says she’s been feeling better lately.

But when she was in the thick of it, choosing between making her bed and getting dressed in the morning was a whole new world for a woman whose default mode was “go.”

“I used to work out. I try to eat well. I’m always active. I’m always busy. I was doing Superwoman stuff, and life went on a pause, literally, shut down for maybe two solid months for me.”

POTS also affected her business. Clarke had her own catering company and used to operate the Free Press cafeteria, which is where we’ve met to talk.

“I couldn’t work,” she says. “I had to hire somebody to do my job. And it was hard enough to be operating a business where, you know, I can’t afford to hire somebody.”

Clarke says she lost the “power to power through.”

“I’ve never been too sick to do anything,” she says.

But living with POTS has rearranged her priorities. She’s doing life in a different way. She’s spending more time with her kids.

“I’ve been trying to be intentional about doing things that are important,” she says.

Clarke had sometimes thought about slowing down. She just wanted it to be on her terms.

Berthelot, meanwhile, has also been managing her POTS. She was salting her food until it became inedible, so has switched to gel caps. She was already wearing the compression socks and taking the electrolytes. She’s finally getting in to see a cardiologist this month. She’s also been seeing an osteopath, who she says has offered some relief.

“It feels like absolute voodoo — it feels like witchcraft,” she says. “But I have to say, I’m finally feeling, I would say, like 80 per cent better, about 80 per cent of the time. If it’s placebo, I don’t care, whatever; take my money.”

Both women say they wish there was more awareness about POTS, among both health-care providers and the general public.

“Nobody knows what it is, so it’s really difficult for your friends and family to understand, because you can sometimes very much present as normal,” Berthelot says.

Clarke, for her part, worries she might still be struggling today if she hadn’t chanced upon a doctor who was familiar with POTS.

“I honestly don’t think it should be so hard to diagnose somebody, you know what I mean?” she says. “Let them sit down, get up, check their heart rate, check their blood pressure. It’s simple.”

jen.zoratti@winnipegfreepress.com

Jen Zoratti

Columnist

Jen Zoratti is a columnist and feature writer working in the Arts & Life department, as well as the author of the weekly newsletter NEXT. A National Newspaper Award finalist for arts and entertainment writing, Jen is a graduate of the Creative Communications program at RRC Polytech and was a music writer before joining the Free Press in 2013. Read more about Jen.

Every piece of reporting Jen produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print – part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.