Throughout his career, Brian Smiley found himself on both sides of many coins.

He’d kept his cool at the centre of scrums surrounded by pressing journalists, decades after being the reporter asking tough questions. His name was printed above the fold many times: first as a byline, later as a representative for Manitoba Public Insurance.

Now, after a lifetime of storytelling, his loved ones remember him through stories of their own.

Smiley died of colon cancer on May 4. He was 68.

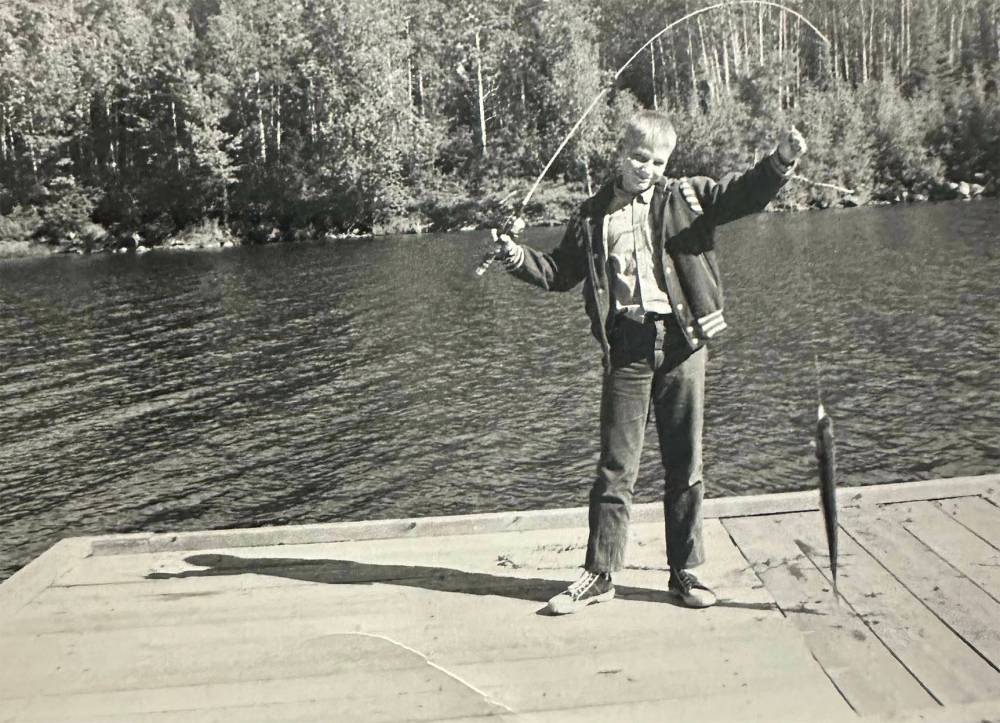

Growing up in the north end of Selkirk, he was fiercely independent early on: he played many sports and would get himself on Beaver buses to Winnipeg for his baseball games by the time he was 12.

SUPPLIED

Smiley knew he wanted to be a sportswriter from a young age.

At 11, he picked up a job delivering the Free Press, and quickly decided he wanted to be a sportswriter.

In middle school, he saved up enough money to get himself a desk from Eaton’s, which he treasured for the rest of his life; it is still with his family today.

“There wasn’t many things that he was sentimental about, but that desk was, weirdly, one of them,” Brian’s son, Lane Smiley says.

He pursued his dream with an unwavering intensity. To pay for post-secondary education, he worked a string of tough jobs, including stints at a steel mill and delivering lumber.

He moved to Alberta to begin his career as a newsman, which took him across the Prairies, from the Spruce Grove Examiner to the Regina Leader-Post and the Calgary Sun, before landing back in Manitoba at the Winnipeg Sun in 1987.

SUPPLIED

Brian Smiley grew up in the north end of the town of Selkirk.

What his family describes as a “gift of the gab” served him well in that time — he interviewed everyone from Teemu Selanne to Wayne Gretzky, reported on a prestigious hockey tournament in Moscow, travelled with Team Canada on a 10-city series of exhibition games, and attended the 1984 Winter Olympics in Yugoslavia.

He covered the first iteration of the Winnipeg Jets and followed the Blue Bombers, but would pick up the pen for just about any sport, even reporting on horse racing for a while.

Before sportswriter Ed Tait was part of the reporters division of the Canadian Football Hall of Fame, he was what he describes as the “No. 2 guy” to Smiley on the Jets beat at the Sun in the late 1980s.

It was a competitive industry, both inside and outside the newsroom, but Smiley immediately became a mentor figure to Tait.

“When you’re a young guy like me at the time, how do you not idolize someone that’s already done it and has been very open to helping you?” Tait says.

“He’s a prince,” he says. “He was a prince of a man.”

Tait remembers Smiley’s “dogged” nature: nicknamed “Smiles,” he was often in the middle of newsroom conversations, making everyone laugh. Then, his phone would ring, a source on the line, and he would go eerily quiet. The chase to get the story (and to get it first) would begin.

“He had a really good relationship with the players, but when there was a whiff of something happening, that’s the guy I wanted on my team, because he was going to get the story, period,” Tait says.

Smiley met Linda in 1989, and the pair married in 1994. They played softball together and sports were a central facet of their family life. Outside of his work, Smiley coached hockey, umped slo-pitch and even taught the craft in Nunavut.

SUPPLIED

Brian Smiley and his wife Linda met in 1989 and shared a love of sports.

He was the vice-president of the Lee River Snow Riders and particularly loved snowmobiling — so much so that his family is raising money to build a snowmobile hut east of Lac du Bonnet in his memory, for other sports enthusiasts to warm up while out on the trail he rode.

When fellow hockey coach Bruce Schmidt went on vacation at the tail end of the 2015-16 season, he decided he could only trust Smiley with his Manitoba Major Junior Hockey League team, the Transcona Railer Express.

Smiley took it on with his typical gusto.

“He came and practised with us, and got to know the guys and wound up putting together a six- or seven-game heater and got us into the playoffs,” Schmidt says.

“It was something, it really was.”

He loved a microphone and a camera, was a gifted wordsmith and a sharp joke-teller. Most who knew Smiley well knew he was a prickly man with a soft interior.

“He would ride or die for his friends, but he had a hard shell to crack if you didn’t really know him,” Smiley’s son, Blake Smiley, says. “He was intense, intimidating, to some people.”

True to his life’s work, however, the truth about Smiley came out through the written word. When a friend was diagnosed with cancer 15 years ago, he’d asked Linda to read the card he’d written. She’s still moved today by how heartfelt it was.

“He had a huge heart,” she says. “I’ll tell you, if he loved you… he loved you hard.”

An avid cottager in Lac du Bonnet, Smiley would snowmobile every winter weekend and watch the boats go by in the summer.

He wasn’t a fan of fishing or golfing, but absolutely loved cutting wood.

“Any time I had something physical, I’d make sure that I would ask him if he was interested, and more often than not, he would show up — so long as it wasn’t too risky,” Stewart Bidinosti, a longtime family friend with a cottage nearby, jokes.

Smiley had a rare wit about him, Bidinosti says.

SUPPLIED

Brian Smiley with wife Linda and sons Lane and Blake.

“He was a communicator, and there’s always different ways to speak and use words, and I think I’ll miss that,” he says.

After the Smileys had their two sons, Brian left journalism in 1998 and became MPI’s media relations co-ordinator and, effectively, its public face.

MaryAnn Kempe sat on MPI’s executive at the time and remembers Smiley as a dear friend who had an “uncanny ability to connect with people.”

“It is not for the faint of heart to be the media spokesperson for a Crown corporation including insurance, and he was a consummate professional,” she says.

He held the role for 25 years from a desk covered with hundreds of newspapers and Toronto Blue Jays paraphernalia.

Whether MPI was facing heat from reporters, or he was putting hours of research into his signature yearly “Top 10” list of auto insurance fraud cases published by the corporation — those lists now so commonly covered by new journalists, it borders on a rite of passage — Kempe said he handled it all with equal care.

SUPPLIED

Brian Smiley with grandson Theo.

“No matter the time, or if it was a weekend, I knew I could always count on him,” she says. “I hope he felt the same way about me.”

After a colonoscopy, Smiley was diagnosed with colon cancer on St. Patrick’s Day in 2022.

He had surgery that June and went through seven months of chemotherapy, but his symptoms returned and quickly worsened over the next year.

In his last days, he was thinking of others, and called on his loved ones to make sure they got a colon check of their own.

Malak Abas

Reporter

Malak Abas is a city reporter at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg’s North End, she led the campus paper at the University of Manitoba before joining the Free Press in 2020. Read more about Malak.

Every piece of reporting Malak produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.