:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/2023/03/10/loyalty-and-affection-is-threatened-in-a-spy-among-friends/20230310110320-640b58e21a7f055a7985ac88jpeg.jpg)

NEW YORK (AP) — A main character in “A Spy Among Friends” is one of the Soviet Union’s most notorious double agents. But you don’t need to know anything about him — or really about spying in general — to enjoy the show.

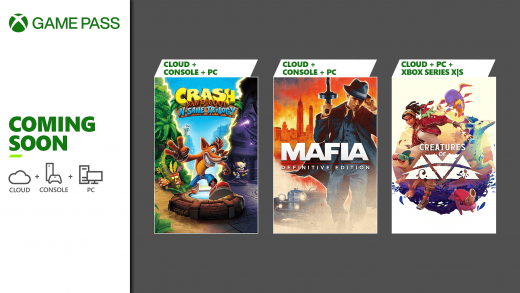

The MGM+ series starring Damian Lewis and Guy Pearce dramatizes the true story of two British spies and lifelong friends, Nicholas Elliott (Lewis) and Kim Philby (Pearce.) The latter became a notorious British defector. But it’s the personal betrayal that the creators hope to explore, not stolen microfilm or dead drops.

“We’re not principally telling a spy story. We’re telling a story about friendship. This is a series about friendship among people who happen to be in the espionage business,” says director Nick Murphy.

Creator and executive producer Alexander Cary and Murphy use 12 hours to unspool this epic betrayal over several decades, moving back and forth in time to capture past conversations and memories.

“I think really we tried to tell an aftermath story here a little bit. So we have tried to dig into the emotional and intelligence and political damage left by Philby,” says Lewis.

It’s anchored by a dayslong meeting between Elliott and Philby in Beirut in 1963, in which both men play a final cat-and-mouse. Elliott wants to extract a full confession; Philby is feigning innocence. The latter will soon flee Lebanon and defect to the Soviet Union, where he died in 1988.

“Philby took a system that really ignored checks and balances because there was just a belief that the system was impenetrable,” says Pearce.

Anna Maxwell Martin plays Lily Thomas, an MI5 agent interrogating Elliott after Philby’s defection, trying to find out what exactly happened between these two men in Beirut. “Could you explain to me why you let the most dangerous Soviet penetration agent this country has ever known leg it?” she asks Elliott.

Thomas — a composite character — is used to signal a change is coming as the old boys’ club gets shaken, charting the rise in the ‘60s of women, people of color and members of the middle class to positions of authority.

“She is representative of the next generation and a different type of person entirely — a woman and not from the social militia these guys come from,” says Lewis. “She is really there to illustrate that it’s time for a change.”

The series is adapted from a book by Ben Macintyre, who also wrote about the origins of Britain’s elite Special Air Service which was recently turned into the series “Rogue Heroes.”

Unlike that kinetic series, “A Spy Among Friends” is more measured, though no less gripping. It’s a series awash in fedoras, clunky telephones and many, many glasses of whiskey. There is pelting rain, the crisp burn of cigarette paper and cups of tea rattling.

Because it deals with people hiding their true identity, small gestures like a raised eyebrow can telegraph what a character is really thinking. Feelings leak out, not gush. In one scene, Elliott secretly weeps about the loss of his friend amid rolliking laughter from among the audience of a stage comedy.

Philby’s betrayal cut deep in Britain’s psyche, more perhaps than American counterparts like Aldrich Ames or Robert Hanssen. Philby was a member of the privileged upper class, who went to the best schools and walked the elite corridors of power.

“He is an example of everything that is appealing about Englishman and also dangerous,” says Cary. “Men of that upbringing were raised with huge levels of entitlement to believe they were the ruling class. That is the scar that England I think lives with today.”

Philby’s charm and guile also embarrassed the United States. He befriended Jim Angleton, a rising star at the newly created CIA who would go on to become its counter-intelligence chief, never guessing Philby was passing on his every confidence to Moscow.

As Philby tells his Russian handler after defecting: “It’s really remarkable the level of sentimentality and arrogance that it must take in order to be so willfully blind to the possibility that one of your own might possibly see things differently.”

Philby pierced the smugness of a strict system, posing a threat to the deluded status quo with the possibility that one of its leading lights was not buying into their project.

“It injures Britain,” says Murphy. “Everything that the class system holds itself up to be and therefore justifies itself with — the arguments that this class of people are honorable, they are trustworthy, they are decent people, they put country first, they put England first — is undermined by Philby.”

On a more personal level, Philby’s deception shattered the decadeslong friendship between he and Elliott. It led Elliott to question whether there was ever a friendship in the first place. It is a show that makes you question all your relationships.

“I don’t think you need to have a Ph.D in British spycraft in order to understand that,” says Murphy. “What keeps you turning the pages in the story is not a regard for the intelligence safety of Britain. It’s a regard for the emotional survival of the characters.”

Fittingly, Lewis and Pearce bonded nicely while making the series. “A Spy Among Friends” marks the first time they’ve worked together and they ended up friends, planning visits. “I’m still waiting for that spare room,” Pearce teases Lewis. Replies Lewis: “The Pearce suite awaits.”

___ Mark Kennedy is at http://twitter.com/KennedyTwits

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

does not endorse these opinions.