George Cotter didn’t shoot to kill. He shot to preserve.

Born in 1915 in Cumberland House, Sask., Cotter revered the natural world. He was driven to school by a team of sled dogs, as a teen he worked the trapline, and after moving to Winnipeg in 1933, he thirsted for the twitter of the whiskeyjack and the first sip of ice water from a winter stream.

In 1950, as the Red River Valley flooded, Cotter climbed onto his St. Vital roof, watching the drama flow past his viewfinder. More than 100,000 residents were evacuated, over $1 billion in damage was caused and the career of one of the province’s foremost naturalist documentarians was launched.

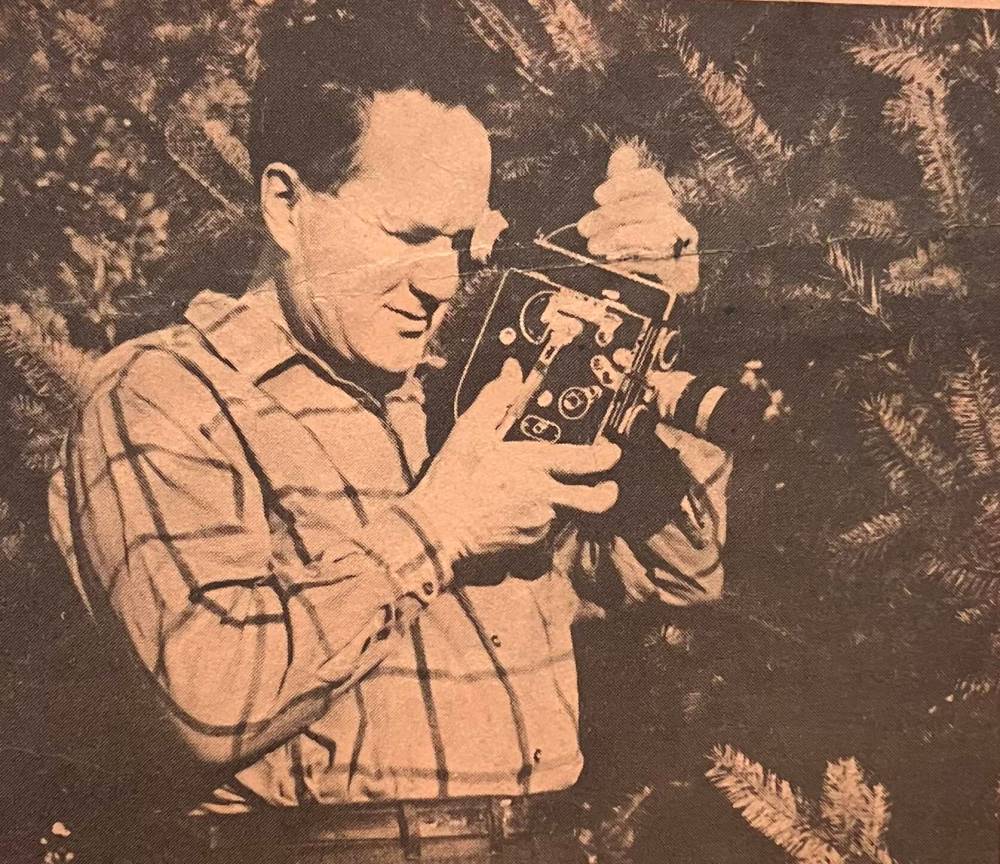

Supplied

George Cotter was the longtime president of the Manitoba Naturalists Society.

From the time George and Sally Cotter started Cotter Wildlife Productions in the late 1950s to George Cotter’s death at 96 in 2011, the longtime president of the Manitoba Naturalists Society filmed dozens of shorts with topics ranging from the great grey owl to cattails to the sealskin footwear of the Inuit.

The Cotters’ reels were shown in schools across the province as supplements. With sharp scripts by Sally, the films were marked by Cotter’s devotion to conservation — of not just the terrain of his youth, but to the rugged ideals of a life in the bush, where animals came first and humans were required to stand at a remove.

“Even in the winter, I prefer to stay outdoors all day, or for several days,” Cotter says in the feature-length documentary Wilderness Trails. “That way I become just one more animal moving through the woods.”

Since its 1976 première, the film has languished in obscurity in the Library Archives of Canada. But on Thursday, a digitally restored version will screen at the Gimli International Film Festival for its first major public showing in 48 years, offering a pair of filmmakers making sense of a landscape they knew wouldn’t last forever.

Before he directed Wilderness Trails, Gunter Henning was shooting commercials for K-Tel.

“There was one for rollerblades without blades, one for a tetherball game, one for the E-Z Tracer,” says his son, Mark. There were also the ill-fated Alaskan clacker balls, pulled from the market after the glass shattered and tears were shed.

Born in Germany in 1929, Henning immigrated to Canada in 1953, editing a newspaper in Flin Flon and working at a photography and music store.

By the 1960s, he was running a 10-person film processing operation called Cine Labs on Sargent Avenue and a production studio called Western Films. Aside from K-Tel, Western Films’ primary client was Manitoba’s department of tourism and recreation. In 1969, Henning’s team produced a travelogue of the province with Esquire magazine’s travel editor, with cinematography by Werner Franz, who edited Cotter’s first film, Wildlife Surrounds Us, in 1961.

Like Cotter, Henning relied on his wife, Frances, for scripts and written copy.

University of Manitoba Archives

Cotter with his camera

Meanwhile, after selling his shares in the St. Vital Lumber Co., Cotter devoted himself to wildlife photography.

“A major part of his life was making people aware,” says his daughter, Liz Morris.

No matter the season, the Cotters camped. On three-week canoe trips through the Manitoban backcountry, the kids learned by observation how to behave in the wild.

“We weren’t allowed to go into the bush screaming and yelling. We had to make sure not to scare living things,” Morris says.

“We couldn’t have dogs or cats because my mom was allergic to them, so we had wild animals instead.”

An injured squirrel named Chippy would sleep under her brother Stuart’s pillow.

“We took him and thought we lost him, but found him sleeping in the hood of a winter coat,” Morris says. “We had a woodchuck and a baby goose and a sparrow hawk named Lady who liked to sit on the stainless steel kettle and stare at herself.”

The Cotters took their shorts — Wings of Summer, an ornithological survey; You Bet Your Life, a practical winter survival guide; and A Poplar Story, about one stump’s biodiversity— on the road, selling reels in English and French to school boards across the country.

Supplied

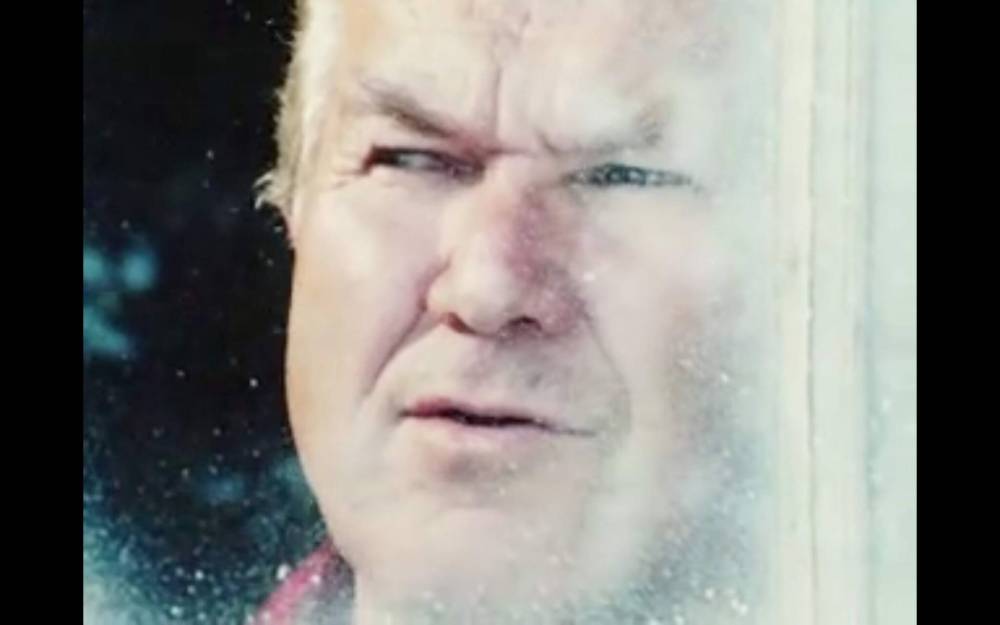

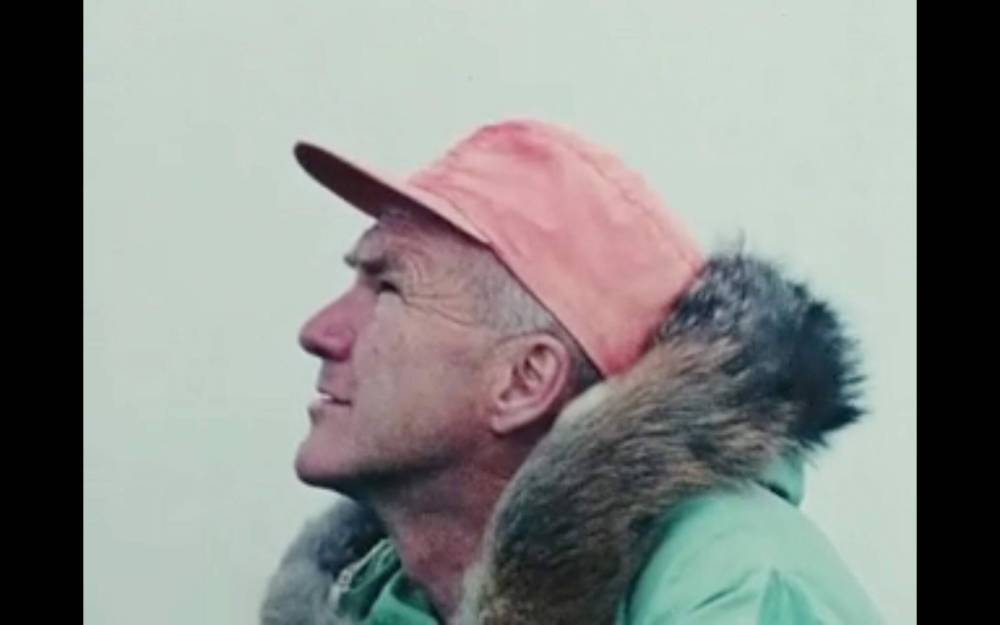

Naturalist documentarian George Cotter from his 1976 film Wilderness Trails

In the mid-1970s, as the National Film Board was achieving success with documentaries and the Winnipeg Film Group began in earnest, Henning and Cotter were connected by Paul Morton and Israel Asper, co-founding partners of CanWest and CKND-TV, which launched in 1973.

“When they needed Canadian content, they approached George about doing a feature-length film,” says the Winnipeg-born composer Victor Davies, who would provide the score to Wilderness Trails. “George had all kinds of stock footage, and Gunter would shoot George as he filmed.”

The resulting film is an 87-minute double-profile, with a 65-year-old Cotter — peaceful, quiet and patient — the only human onscreen. He chops wood, dipping himself into a plank position to take two sips from a gently burbling stream.

“You can’t beat the feel and taste of those first warm spring days,” he says.

Henning’s footage of Cotter is spliced in by editor Ed Smith to present the naturalist as a parallel creature. When Cotter cooks himself bacon, a squirrel nibbles on his own food.

“They share my lunch with me from a safe distance.”

And it’s the animals, bolstered by Davies’ score, who rightfully steal the show.

The western grebes, Cotter says, “are the Fred Astaires of the water,” scampering for 50 feet before beginning to swim. The sharptail grouse stomps its feet like a drummer on beat. The sage grouse performs a mating dance, filling its throat sac and hoping to earn a shot at procreation.

Cotter was always aware that many of the creatures were under threat of disappearing, not just from their natural habitat, but from the visual and cultural record of Canada.

Supplied

George Cotter’s filmmaking was motivatred by a reverence for the natural world.

“It’s desperate,” University of Alberta ecology professor Mark Boyce told the CBC in March of this year when discussing the sage grouse. “They are going to go extinct, it’s almost certain.”

There are fewer than 100 alive in Canada today.

In Wilderness Trails, Cotter captures about a dozen in a single frame.

The credit for reintroducing Wilderness Trails, and George Cotter, to a new generation is owed to local documentarian Kevin Nikkel, who came across Cotter’s name about three years ago.

All he could find of Cotter’s work was a short clip on YouTube, so he contacted the Library Archives in Ottawa, where he found a feature print of Wilderness Trails.

Nikkel, who did his own conservation work with Establishing Shots, an oral history of the Winnipeg Film Group, and the feature documentary Tales from the Winnipeg Film Group, was interested in Cotter and Henning because their careers existed outside that independent filmmaking universe.

The work itself was a gem, says Nikkel, who felt he had struck archival gold. Even on the low-resolution version, it was clear Wilderness Trails had both artistic and historical merit.

So Nikkel, a programmer for Gimli, thought the film deserved a renewed audience.

Supplied

Naturalist documentarian George Cotter from his 1976 film Wilderness Trails

“I said, ‘Can we squeeze in this film that nobody’s heard of and has long since been forgotten?’”

Several Cotter reels were recently donated to the University of Manitoba archives by Liz Morris, and Nikkel hopes to see them somehow.

“Maybe we can put on a Cotter Film Festival at the Cinematheque.”

Ben Waldman

Reporter

Ben Waldman is a National Newspaper Award-nominated reporter on the Arts & Life desk at the Free Press. Born and raised in Winnipeg, Ben completed three internships with the Free Press while earning his degree at Ryerson University’s (now Toronto Metropolitan University’s) School of Journalism before joining the newsroom full-time in 2019. Read more about Ben.

Every piece of reporting Ben produces is reviewed by an editing team before it is posted online or published in print — part of the Free Press‘s tradition, since 1872, of producing reliable independent journalism. Read more about Free Press’s history and mandate, and learn how our newsroom operates.

Our newsroom depends on a growing audience of readers to power our journalism. If you are not a paid reader, please consider becoming a subscriber.

Our newsroom depends on its audience of readers to power our journalism. Thank you for your support.