:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/television/2022/10/29/the-crown-controversy-is-the-royal-drama-a-malicious-recounting-of-history-or-just-escapist-tv-heres-why-the-distinction-matters/charles_and_diana.jpg)

The fifth season of “The Crown” won’t be released until Nov. 9, but that hasn’t stopped the denunciations.

“Damaging and malicious fiction” and “a barrel-load of nonsense peddled for no other reason than to provide maximum — and entirely false — dramatic impact,” is former British prime minister John Major’s scathing reaction to reports that “The Crown” includes scenes of him and Charles plotting in regard to a possible abdication of Queen Elizabeth II as well as Major disparaging the royals to his wife.

Then George Carey, the former Archbishop of Canterbury, complained after being told of a scene in which the late Queen confides to him that the failure of three of her children’s marriages “begins to look like parental failure of the most awful kind.” Carey said, “It bears no resemblance to any conversation I ever had with the Queen.”

Netflix has added the descriptor of “fictional dramatization” to its Season 5 trailer, a label that wasn’t necessary in previous seasons; it is now, since its plots involve events well within living memory, and because people near to the Royal Family are raising concerns about the damage that such a lavishly detailed drama is inflicting on their image.

On Oct. 20, Dame Judi Dench, a friend of King Charles III and Camilla, Queen Consort, shot up a flare in a quintessential British manner, via a letter to the editor of the Times. “The closer the drama comes to our present times, the more freely it seems willing to blur the lines between historical accuracy and crude sensationalism,” wrote Dench, who has portrayed both Queen Elizabeth I and Queen Victoria during her long acting career. “I fear that a significant number of viewers, particularly overseas, may take its version of history as being wholly true.”

The risk is as impossible to ignore as the series itself, and a worry shared by other observers. Royal biographer Robert Hardman, who mentioned or wrote about the series in 16 pages of his newest book, “Queen of Our Times,” told the Star that “as the plot moves ever closer to the present day, this will have an increasingly corrosive effect on the way the world views today’s Royal Family.”

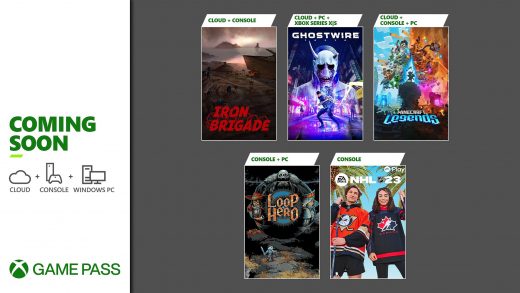

Inspired by real events, this fictional dramatisation tells the story of Queen Elizabeth II and the political and personal events that shaped her reign.

There is data to support those concerns. An Ipsos poll released in March 2021 shows the impact of “The Crown”: 71 per cent of American adults who are aware of the series believe that it is realistic, with more than one-third of the key 35- to 54-year-old demographic believing it is very realistic. Even Prince Harry has said that “The Crown” “gives you a rough idea of that lifestyle, of putting duty and service above family and everything else.”

“I worry that people with only half an eye on royal events will swallow fiction as fact,” explains royal biographer and commentator Christopher Wilson. Fact-checkers, including royal authors, have pointed out many incidents of dramatic licence in “The Crown,” whether it’s Queen Elizabeth II being so lacking in emotion that she fakes tears at the Aberfan disaster (not true); a young Prince Philip being blamed for the death of his sister and her family (absolutely not true); or the royals being deliberately rude to Margaret Thatcher during her first visit to Balmoral Castle (nope, sorry).

However, “The Crown” and its royal narrative are tough to fight, especially when it’s virtually impossible for anyone without an encyclopedic knowledge of royal history to separate what happened in real life from the 50 hours of scenes created in the mind of writer Peter Morgan. Like many experts, Hardman has seen how hard it is for viewers to differentiate fact from fiction. “‘Oh it’s only a drama, it’s only a drama,’” he recounts people saying, “and then five minutes later you hear them say, ‘Well, mind you, they were pretty mean to Mrs. Thatcher.’ Oh, there we go.”

There is certainly a symbiotic relationship between fictional and real royals. After Elizabeth’s death in September, viewership of “The Crown” increased by 800 per cent in the U.K. and quadrupled in the U.S., Variety reports. And some observers, including a few Hardman interviewed for his latest biography, have more encouraging things to say about the effect of the series on the actual monarchy.

“I have no way of knowing how accurate it is, but it is good PR,” Joseph Nye, a professor at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, told Hardman. Former U.S. president George W. Bush was likewise complimentary, “I thought Her Majesty comes across well. It’s an interesting portrayal of her,” he is quoted in the book as saying.

Hardman’s take is less positive.

“Every important public figure can expect to be dramatized at some point. Fine,” he states. Still, to him, the drama goes too far. “‘The Crown’ not only fictionalizes the lives of people still in their public roles but wilfully distorts the truth,” he says. “Suggestions that, say, the Queen deliberately conspired to undermine Mrs. Thatcher’s government or that mentally disabled Bowes-Lyon cousins were locked away on royal orders to shield the monarchy from scandal are not reinterpretation of events. They are, simply, deliberate falsehoods. Personal reputations are casually trashed along the way.”

(The Toronto Star reached out to Netflix about the issue of fact versus fiction in “The Crown” but received no response.)

Megan Judt has watched the series from the day it launched in 2016. “I was so excited for it and I loved it so much,” says Judt, 36, a fundraiser who lives in Alexandria, Virginia. She too has seen how people confuse the drama on the screen with real life.

“Everybody talks about how they (Queen Elizabeth and Prince Philip) were such bad parents, and she was so unaffectionate and unloving to her kids, and then you watch the funeral and you hear the tributes from the kids,” says Judt. “It’s hard to believe that their childhood was that emotionally starved and she was that emotionally limited if all of them are absolutely gutted.”

While there’s no doubt that “The Crown” is a riveting dramatic series, part of the problem is how brilliantly it reconstructs the royal world and its past. Enormous detail is paid to which tiaras and gowns were worn at specific state dinners or even the tchotchkes on Elizabeth’s desk, which combine to give the impression of an abiding faithfulness to the historical record.

Its writer-creator, Peter Morgan, may well have an axe to grind; a staunch republican, he has compared the royals to a “mutating virus” and described Elizabeth as “a woman of limited intelligence.” But he has also talked about the painstaking research done by a team of historians and researchers that underpins his writing. That credibility is buttressed by its use of top-rate actors — in the new season, Elizabeth is played by Imelda Staunton while Jonathan Pryce is Philip — and by the lush sets and locales that feature so prominently in the series.

Set in the 1990s, the fifth season will plunge a whole new generation into what was the most turbulent decade in the monarchy’s modern history. In 1992 alone — dubbed her annus horribilis by Elizabeth herself — the marriages of three of her four children ended; a tell-all book revealed shocking allegations from Diana’s side of her unhappy marriage; Windsor Castle burned; and the Queen agreed to pay taxes for the first time.

It was also the worst decade of Charles’s life. Rarely a week went by without another instalment of the War of the Wales, as his marriage to Diana imploded in public acrimony amid claims of infidelity and cruelty. Diana won the media war; Charles was eviscerated for his affair with Camilla, now his wife of 17 years. It took decades to rebuild his reputation. And now, as he settles into his new role as monarch, those wounds are being ripped open once again in living rooms around the world.

There’s little that the royals can do. “They just have to grin and bear it,” says Wilson. “I feel sorry for them in that respect.”

Judt is unsure whether she’ll watch the new season. Like many, she uses dramas as an escape. Though she loved the early seasons for their interesting historical drama, she slowly lost interest as it became more negative and, in particular, how its villain seemed to change from the institution itself to the Queen and then Charles. “God only knows who it will be in this season, maybe all of them,” she says. “I don’t understand what they want me to walk away thinking about the monarchy and the people inside of it, unless it’s that they want me to hate them.”

JOIN THE CONVERSATION

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/television/2022/10/29/the-crown-controversy-is-the-royal-drama-a-malicious-recounting-of-history-or-just-escapist-tv-heres-why-the-distinction-matters/turn_1.jpg)

:format(webp)/https://www.thestar.com/content/dam/thestar/entertainment/television/2022/10/29/the-crown-controversy-is-the-royal-drama-a-malicious-recounting-of-history-or-just-escapist-tv-heres-why-the-distinction-matters/turn_2.jpg)